Survival in low oxygen environment: Investigating mechanisms of short-term plasticity and long-term genetic adaptation

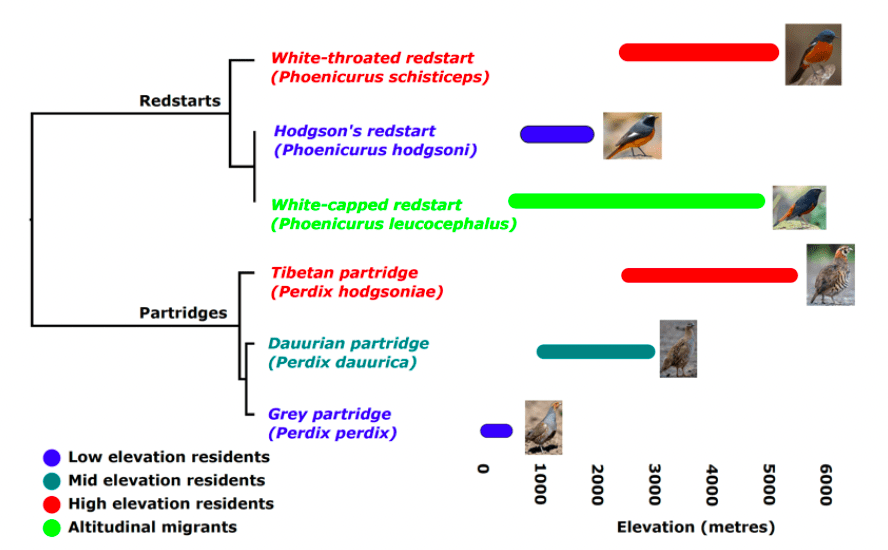

One of the key questions in evolutionary biology is to understand how an organism responds to a novel environment. Two major evolutionary processes that allow organisms to adapt to a novel environment are (1) phenotypic plasticity and (2) genetic adaptation. These two are mostly studied as separate independent processes, and the possible synergistic effects of these two processes in facilitating or hindering adaptation have received less attention. We are studying multiple species of birds residing across the steep elevational gradient of the Himalayas, and quantify a suite of physiological traits that show plastic and adaptive response associated with changes in atmospheric oxygen levels across elevation.

Molecular mechanisms underlying microbiome-mediated dietary adaptation

One of the ways in which a species can adapt to its environment is by maximizing the use of available resources, e.g., introducing new food sources into the diet. The gut microbiome, which plays a key role in host digestive processes, can thus become one of the strongest determinants of dietary adaptation. We are studying pikas (Ochotona sps), herbivores that are adapted to high-altitude environments and demonstrate considerable dietary flexibility across their habitat range. We use an integrative approach that leverages multi-omics methods to examine functional relationships among the pikas, their gut microbiome, and the environment.

Biology of invasion

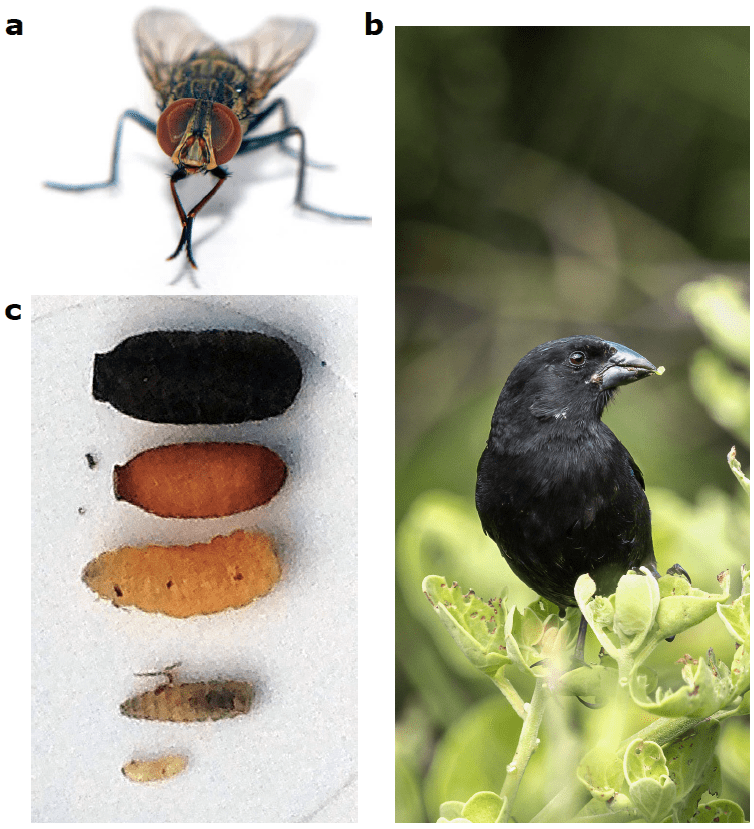

Invasive species are of increasing concern for global biodiversity, as they disturb local community structure and in extreme cases, may even lead to the extinction of native species. The invasive avian vampire fly (Philornis downsi) is considered one of the greatest threats to the unique and endemic avifauna of the Galápagos. The fly parasitizes nearly every passerine species, including Darwin’s finches, in the Galápagos. We are studying various populations of Philornis downsi from multiple islands of Galápagos to examine the evolutionary pathways of invasion.

Mechanisms of hybridization and speciation

Hybridization between animal species in nature was once thought to be rare and of little evolutionary importance. But, this view has been overturned by discoveries in a wide range of taxa, especially in the past two decades, thanks to our increased ability to study the full-scale genomes of a variety of hybridizing natural taxa. We are studying the genomic consequences of ongoing introgressive hybridization between different species of Darwin’s finches in Galápagos.

Collaborators

Internal collaborators at Kent State University

- Dr. Laura Leff

- Dr. Xiaozhen Mou

- Dr. Srinivasan Vijayaraghavan

- Dr. Sanjaya Abeysirigunawarden

- Dr. Wilson Chung

- Dr. Rafaela Takeshita

External collaborators

- Peter Grant (Princeton University)

- B. Rosemary Grant (Princeton University)

- Scott Edwards (Harvard University)

- Jennifer Koop (Northern Illinois University)

- Shane Dubay (University of Michigan)

- Sarah Knutie (University of Connecticut)

- Jaime Chaves (San Francisco State University)

- Leif Andersson (Uppsala University, Sweden)

- Nan Wang (Beijing Forestry University, China)

- Bhoj Kumar Acharya (Sikkim University, India)

- Nishma Dahal (Institute of Himalayan BioResource Technology, India)